|

Agnes Sells |

|

|

|

The following

is a story that was handwritten for me by Agnes Sells, a native of the

country of Estonia. It’s a remarkable story of a very courageous person.

The dangers she faced and dealt with during the invasion of Russia in

Estonia are horrifying. Here is her story, just as it was written in her

own words:

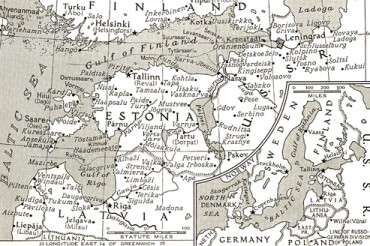

“I was born in Tallinn, Estonia, a small country off the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. South of us is Finland, east of Sweden and West of Russia. Estonia is a small country. It’s larger than Denmark, Switzerland, or Belgium. It’s also so-called the land of midnight sun at summer time. But at winter is visa-versa. We are Finnish descent; our language are very similar to Finnish, but nothing like German, Russian, or French. |

|

The Red Army, or Russians, marched into Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) in early 1940 with promises to protect us, and being a country surrounded by the sea, Russians had a clear view, like us being the window of the world. After their arrival, all kinds of orders were issued. To list all the names you corresponded outside of Estonia. All radios confiscated and I can’t remember what all. Then, overnight, our money was exchanged in banks. For example, if you had let’s say a dollar in bank, you were given something over 100 rubles, or if you had thousands of dollars, the same amount. All businesses taken over, your houses, if you owned one, farms, they become collective farms. People started to disappear and no trace, they were arrested, tortured, murdered, etc. You weren’t safe anywhere and, as it was said, ‘it wasn’t safe to sleep two night in same place.’ Then in June 13 and 14, exactly at 1 a.m., at gathering points, the trucks started to roll to the homes to the addresses given. At that time at night, most people being fast asleep being awakened by loud banging at the doors. At times doors were pushed in, several soldiers who ordered them to get up, get dressed, and packed some of their clothing. Families were taken: women, children of all ages, and men. They were taken to railway stations where trains were ready to load them into cattle cars. My parents were among them. My brother, Harry, was able to jump out of the window when the loud banging was at the door. I lived several miles away from my parents’ home. By running and sneaking through the streets, he (Harry) reached me, white as a ghost, asking for help or something. We were like sheep without their heads. For a while we were hidden by friends, then later taken to the country to our deep forest. Meanwhile those loaded in trains stayed in railway stations for two days. No soul was allowed to get near them; they were heavily guarded. You could hear screams, crying, children whining, cars were loaded full. Men were separated from their families, women and children were together. When trains finally started to move, we all were running along as far they got out of sight. Many letters were thrown out the window (or small corner of the car). We gathered them all, delivering to the addresses given. While we were hiding in the woods, it was dangerous. You couldn’t cook the food, smoke being the giveaway. Our so-called scouts located farmers near by. They left some food, mainly boiled potatoes and bread, at the edge of fields. One day, as I and my brother, Harry, were going to find some food, we got spotted. Hail of gunfire started, we run as fast that our feet never touched the ground at times. I didn’t even know that I had been hit by bullet in my thigh. I was operated later; we had to move out in hurry. We lived in woods about over three months. Then the German army came, pushing the Russians out. Germans we felt at time were our liberators. We were able to return back to our homes, if you had one left. Mostly all the young men, also my brother, Harry, volunteered into German army to fight only against Russians in Russian front. One time he was captured but able to escape. The second time he was wounded, being hospitalized, then give home leave. Then he decided not to return to his regiment, but to go hiding since Germany was losing heavily the war. Somehow, somewhere we decided to go to Sweden. Harry and more people had located a fishing boat. I was to raise money to get the oil, etc. Meanwhile the heavy bombing continued in our city. One night the heaviest began. I was working in government building. Usually Russians came to bomb on clear nights. I decided to stay in the building in the bomb shelter on those nights, but all came so suddenly we didn’t get a chance to get out, but go to basement or a fireproof room where important documents were kept. There we could feel the earth tremble as the bombs fell. We had to get out of there in case being hit. That would have been our grave. We had to cross the courtyard. It sounded like it was hailing, guess it was fragments of the bombs. The sky was full like Christmas trees, it was so bright of light. Then a smoke ring was encircled around the government building and its surroundings, but the wind was heavier than they calculated and carried that smoke ring away from us. The main street below from us was completely demolished, but I made into shelter with the help of others. The hospitals did not have any mercy from the bombs. The fire was everywhere. You couldn’t find you way through the streets. There were no simply any houses left, everything was gone. Someone bigger was watching over me, to come through all that. Then came the final day closer. I didn’t have any contact with my brother, no communication, no transportation. Everything had ceased, and I still didn’t know what to do with myself. One day I was leaving, second day I changed my mind, I was always waiting for that 11th hour. I left my country September 19, 1944. The Germans were leaving and Russians very close. Then I decided to go and in a hurry, throwing clothes in my light suitcase made of plywood, just for storage purposes. There were things I could not crush to pack, because in my mind, I would be back home by Christmas; the war surely would be over. German ships took as many of us and more on their ships. Everyone was escaping the memories of the brutality by Russian hands which had touched all of us. We were overloaded – ship being built for 2,000, we doubled that. At the North Sea, we were bombed and torpedoed. Someone bigger than I was again watching over me. But the next day, more ships leaving Estonia. One was hit and mostly half of the escapees did drown. We landed in Danzig, Germany. We were at sea two days. It was also then Estonia was overpowered by Russians. I was so homesick, if I could be like Jesus, able to walk on water, I would done that. All our passengers landed on the shore, my poor suitcase busted. Luckily, I had tied a blanket and my mother’s feather pillows, saved my treasures being spilled out. We had to find work to be able to eat. Employment office gave us two choices: farm work or ammunition factory, but meanwhile we did visit a small town where the Messerschmidt airplane factory was in Ober-Ammergau. But we didn’t even get the permission to stay there; it was off limits to all foreigners. The nuns were good to us, housing us to a schoolhouse, floors covered with straw. That was the best bed I ever had in long time. Well, my girlfriend and I choose to take the farm job. She started to work in convent and I in a small farmer’s family. The next morning I was handed a pail to go to milk. People there had a good laugh. I always were afraid of cows while on vacation in country. So they started to give me odd jobs like once cleaning a chicken coop, pig’s sty, all that good stuff I didn’t know existed. We stayed there about one month, then moved to join some of our Estonian friends to Bad Blankenburg, Thuringen, the Black Forest. I stayed there till the war ended in May, 1945. The morning end of the war, we have orders to hang white sheets out of the windows, a sign of surrender. The Americans had problems with us, as we didn’t want to go back home we were put in camps. The first meal was wonderful. I’ll never forget that huge army kettle outside filled with green pea soup full with ham meat. We ate so much of it. We were moved from one place to another and we were scrubbing these places festered with bed bugs, saying we have cleaned half of Germany! Finally we get stabilized. First, I worked with a Hungarian doctor. He was looking for the burned SS marks under the men’s arms or in the groins. So they who had them were taken somewhere, I don’t know where. Then I went to Munich where the famous concentration camp had been. I worked there in office building. I was able to visit all these horrible sights where prisoners were kept. It was heartbreaking. The smell of burnt flesh or bones. The furnaces were still there. Many years later, my husband, my son, and I visited Camp Dachau. There was nothing left of the horror what was once there. But we have some pictures of earlier years, what Americans saw turning the liberation. My grandmother and aunts lived in east Germany. I went to visit them during Christmas time. After my visit returning back to my camp, I was suppose to change the trains outside Stuttgart, but I fell asleep and I was awakened when train was moving. The conductor saying I was supposed to got out, now we were going to French section and I’ll be arrested. He said for me to get out in next stop, so I did. It was smallest station I ever seen. I was told since they closed the station and being the last train through, for me to walk across the field, he pointed back to Stuttgart, so I did. But when I reached the river, I believe its name was Nectar, I could not find a bridge. Being at midnight, I couldn’t dare to knock on someone’s door for directions. Traffic was heavy by army vehicles. I was always hiding from them. Then I came to the bridge the train I was on crossed. The river was rough and full of crushing icebanks. I had to get across that wide river to catch my train to Camp Dachau. Then remembering the guy at the railway station saying that no more trains were coming through (what he meant the passenger trains). I had to get across, so I started by pushing my suitcase in front of me, being on hands and knees, going inch by inch, crossing that wide rough river. Below me was most awfulest crushing sound of the icebanks. Finally seemed forever and reached the other side, thanking God again for keeping me safe and secure. I rested on the river bank for seems like minutes, when suddenly a freight train came crossing that same bridge I just seems like minutes I had crossed. While working in Camp Dachau, I started to write home through Kermit, my husband-to-be. He sent the letters to his sister, Allie, in Pennsylvania. She mailed them to my mother, which she done visa-versa. Letters were never signed like ‘Dear Mother’; letters were censored. It was like some old friend. But at least she knew I was alive. After we got married, it still continued. But when Russian dictator Stalin died, we started to call us again ‘Dear Mother‚ Dear Daughter’. I was able to visit my homeland twice – 1978 and 1981 – to see my old parents again since they were deported and stories of life they told me. Dad and Mother were separated and when their journey ended, they were simply dumped into the wilderness with nothing. The hut or huts were already occupied, but like they say, there is still room for one more. How they survived is beyond me, living by frozen potatoes gathered from the uncleared fields. Many died. First the ones living in huts thought that they (my parents) were spies because their clothing and appearance was better or something. When war was ended I can’t remember if she said when that was, finding Dad and getting home again.” I pick up the rest of Agnes’ story from this point on. There were times while Agnes and a friend of hers were in one of the camps that they slept on top of their suitcases and used tin roofing to cover themselves with. Everywhere they went, they were surrounded by barb wire fences, and on one occasion, an opening in the fence was discovered which happened to be near a stream. It was necessary to crawl through a field in order to get to the stream, but Agnes and some others did this in order to bathe in the stream. They risked being shot if they had been caught outside the barb wire area. After the arrival of the American soldiers in Germany, Agnes became acquainted with a U.S. soldier named Kermit Sells, who was serving in the Army at that time. She got to know him through her girlfriend, who worked as secretary for his commanding officer. Kermit went back home to Tennessee in August of that year, and in October, after going through a great deal of paperwork, Agnes immigrated to Canada. Kermit had given her his address and she wrote to him. He came to see her in Canada on two occasions, and in January of 1950, they were married. Two years later, their son, Kermit D. Sells Jr. (“Butch”, a nickname his father gave him) was born. It took five months for the paperwork to be processed in order for Agnes to be allowed to come to the United States. Letters were written to Germany to find out things about her, such as whether or not she had ever been arrested and to learn if she had been exposed to any kind of diseases. She had almost given up hope, waiting is always long, when finally she was approved. Kermit served in the military for 20 years, which meant they had to move a lot. States they lived in were New Jersey, Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Virginia, Louisiana, and they also spent three years in Italy. During his time in service, Kermit also served in the Korean War. Upon his return, he retired, and they made their home in the Oak Grove Community, between Livingston and Alpine. Agnes, against the advice of her husband, took a job at the shirt factory, even though Kermit told her she wouldn’t last two weeks. But she proved him wrong. She worked there for 18 years. Kermit died in 1992, and after his death, Agnes moved to the apartment where she now resides. She has been active in the Eastern Star, where she served as past matron. She is a member of the American Legion, the VFW, and also First Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Livingston. Along with her son, Butch, and a daughter-in-law, Teresa, she has three grandchildren, Whitney, Cody, and Tyler. She also has a beautiful Himalayan kitty cat named Taz who is a very important member of her family, too. Although Agnes has lived in Tennessee for a good many years now, there is not even the slightest trace of a southern accent in her voice. She still speaks with a very distinct dialect of the country she grew up in that can be very easily be mistaken as German by folks such as myself who are not very educated in foreign languages. There were times when listening to her as she looked back on her life the afternoon I visited with her that made me catch my breath, still the sound of her voice was something I enjoyed very much. Agnes told me she likes living in Livingston better than anywhere she has ever lived. People here have always treated her extremely nice and have been nothing but very kind and friendly to her. She has a great deal of friends here as well as other places. Her strength and ability to live through such a horrible time in her life are something that is more than just admirable. Her story makes the everyday problems we often encounter from time to time seem insignificant when compared to what she’s overcome. She lived through a terrible time, and I suppose one of the worst things she has suffered was losing her brother. She has never known what happened to him, and that’s probably the hardest part… not knowing. Thank you, Agnes, for sharing your story. Your spirit and determination in the face of danger are truly an inspiration. I feel honored to have your story included in my journal.

|

|

|

Agnes at Age 14 |

This photo of Agnes’ parents, Alexander and Selma Schmidt, was taken on their wedding day.

|