Elizabeth Myers, Bernice Ledbetter, and Arley Poston were three teachers Bruce remembers having at Fredonia. Because traveling a dirt road to the Fredonia school by car was very difficult then, teachers would park near the Jim Brown home about two miles from Livingston’s city limits, and then walk across the field and up a very steep hill to get to the school. When Bruce was in the fifth grade, he began attending school at Livingston. And to get to school, the Barnes children walked up and down Rock Crusher mountain every day.

A typical day in the Barnes’ home began with getting up before daylight. Cora Barnes always got a fire going in the cook stove first thing, while Quitman went out to the barn to begin whatever chores he had to do that day. All the family sat down together when breakfast was ready, and afterward, the children got on their way to school. The rest of Cora’s day was spent milking the cow, working in the garden or out in the fields, cooking a noon day meal, or if it was wash day, getting the laundry washed and out on the line to dry. The washing was always done with homemade lye soap on a rub board. The ironing was done with a flat iron heated on the cook stove or fireplace. After getting home from school in the afternoons, one of the chores the Barnes children and their mother frequently did was to go to the woods and gather wood for the cook stove. Everyone sat down together once more each night to share the supper time meal.

The fireplace in the rock house where the Barnes family lived was built by Harry Springs, a well known rock mason of African American descent, who also lived on Rock Crusher mountain. Bruce described the house as being very cold in the winter months. Drinking water would be kept in a cedar bucket in the kitchen with an aluminum dipper. If the dipper wasn’t taken out at night during the winter time, the next morning it would be frozen in the water bucket. The kitchen was papered with newspapers, and Bruce recalls looking at an advertisement from part of the newspaper that was over the wash stand in the kitchen. That particular ad listed the price of good and choice hogs as going for three cents a pound. Folks who had farm animals sometimes found it necessary just to give pigs or calves away because they couldn’t afford to feed them. During the spring months, the Barnes children would dig May Apple roots and sell them in order to buy feed for chickens that had been ordered through the mail. Salt, sugar and oats were the only staple items the Barnes family bought from the store. Everything else they ate was raised on their farm.

The first registered Angus cow Quitman Barnes had was one he bought from M.J. Qualls. The cow was given the name Cleva, and it seems that she didn’t like the idea of moving from downtown Livington to the Barnes farm on Rock Crusher mountain. On two occasions, she jumped the gate and went back home to the Qualls house. After bringing her back the second time, she must have decided that she might as well stay put. It wasn’t long before Cleva learned how to open the barn door and the gate to the yard. One day after watermelons had been gathered and brought to the north side of the house to cool, Cleva opened the gate to the yard, and when the family returned home for a planned watermelon feast that afternoon, Cleva and the other cows had eaten up most of the watermelons.

Something Cora Barnes often cooked for the family to eat at breakfast was wheat. The process to get the wheat soft enough to eat took some time. The grains were soaked and then cooked through at least three meals. When it was ready to eat, the wheat remotely resembled puffed rice, and was sweetened with molasses or sugar. Butter could be added too.

Late one afternoon, Bruce was sent to take a message to an uncle who lived near the Fredonia church. By the time he started back home, it was getting dark, and he knew he would have to walk by the graveyard at Fredonia if he went back the closest way. In order to avoid passing a graveyard after dark, he took the long way home, and got back quite some time after dark. On another occasion, he was sent to Casper Bowman’s house way out in Copeland Cove to get a bucket of molasses. That was a very long walk from the Barnes farm to the Bowman’s place, and again, it was completely dark by the time he made it back home with the bucket of molasses.

Bruce remembers how on his 13th birthday, he had spent all that day shocking hay. But that day ended with a surprise from his dad. To mark his 13th birthday, his dad gave Bruce his very first pocket watch.

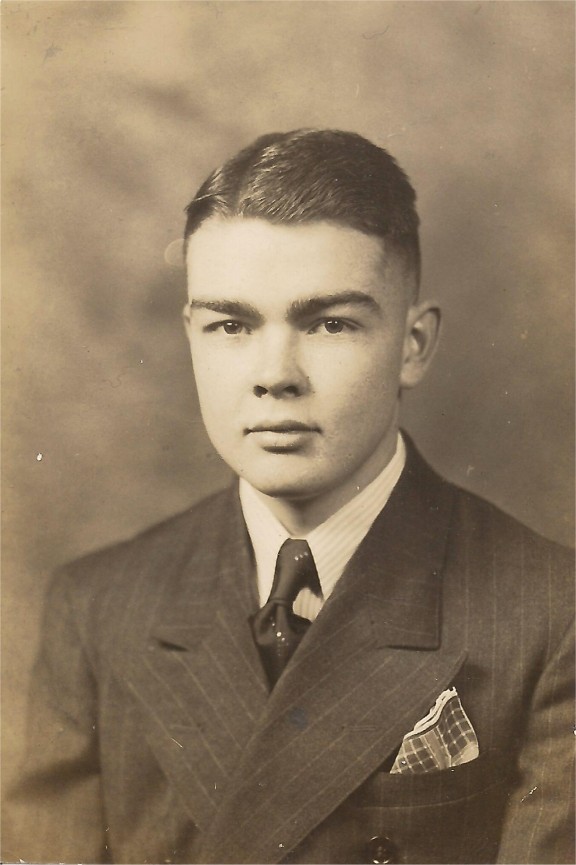

Bruce Barnes was member of Livingston Academy's 1945 graduating class.

Nearing the end of World War II, and the day before Bruce left home for military service, the Barnes family was devastated when word was received that Aldon, an Infantry Staff Sergeant, had been killed in action in Germany. He is buried in Luxembourg Military cemetery. General Patton, under whom Aldon served, is also buried there. Bruce graduated from Livingston Academy in 1945 and ten days later, reported to Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia for basic training with the U.S. Army. It was on Friday, the 13th, that thirteen young men, including Bruce, left to begin serving in the military. Two others in that group of thirteen were Dillis Benson and James McCormick. Bruce’s tour of duty included parachute training with the 11th Airborne Division. Almost a year of his time in service was spent in Japan. On one of his letters he sent home to his parents he had written these initials on the back of the envelope ... Y B S M B Y T. Translated, this said: "You’ll be seeing me before you think." And sure enough, when he got back to Livingston after being discharged, he unexpectedly ran into his father on the square. What a happy reunion that must have been.

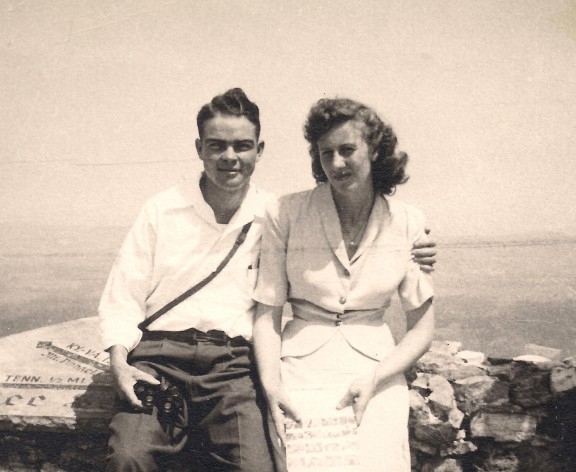

Bruce and Orvie Ruth Barnes were on their honeymoon when this picture was at Lookout Mountain in April of 1948. Note Bruce's resemblence to actor Audie Murphy in this picture

In the spring of 1948, Bruce graduated from Nashville Auto-Diesel College, and on April 22 of that same year, he and Orvie Ruth Little, a young lady he had frequently watched playing basketball on Coach Elmo Swallows’ team at Livingston Academy, started their married life together. Orvie Ruth is the daughter of the late Verdie Little and wife Nettie (Langford) Little. The young couple started out living with her parents, and then later that winter, moved to Rock Crusher mountain to live in a rent house that belonged to Bruce’s father. For the next few years, Bruce made a living farming. Orvie often helped out, especially when it was time to drive the tractor to take up hay. In 1950, Carol Ann, their first daughter, was born, and only two short years later, Bruce got some terrible news. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Due to the fact that there were no beds available, he had to wait three or four months before he could get in at the V.A. Hospital in Nashville for treatment. During that time of waiting for a bed, Dr. Myrtle Smith made regular house calls to see him. When space finally became available, Bruce spent the next eighteen months being treated at the V.A. Hospital in Nashville. The first eleven of those months, he was required to have complete bed rest. Gradually he was allowed to get out of bed for an hour a day. Occupational therapy classes were available for patients while they were being treated, and included different types of handwork, basket weaving, and working with leather.

During the time Bruce was hospitalized in Nashville, Orvie Ruth and daughter, Carol Ann, moved back home with Orvie’s parents. A small cottage type home nearby was converted for Orvie and Carol Ann to live in. Orvie’s parents eventually built a new house just down the road, and after Bruce was well enough to come home from Nashville, he, Orvie Ruth, and Carol Ann moved into Orvie’s parents old home. Their second daughter, Brenda, was born in 1955.

One of the recommendations the treating doctors gave Bruce upon his discharge from the V.A. Hospital was that he change jobs. Dillis Benson offered him a job working in his furniture store, but knowing that job involved lifting a lot of heavy items such as refrigerators, Bruce didn’t think he would be able to handle that type of work. Hoping to maybe get a job in carpentry, he went to see Frank Linder and then Byrd Dillon, both well known and well respected builders in this area, but neither one had enough work to hire him. Around this time, an uncle of Orvie’s, Elmer Langford, a carpenter, recommended Bruce for a job helping with the construction of Memorial Baptist Church. He was hired doing common labor at .75 cents an hour, and later raised to $1.00 an hour. When that job was finished, Hack Roberts suggested Bruce get in touch with Paul Masters to see if he might have work for him. Paul put Bruce to work the same day he went to see him for $1.25 an hour. He continued on with Paul Masters until another illness brought on from breathing creosote fumes while treating a house for termites put him in the hospital for five days. After being discharged, he spent the next six weeks in bed. He later learned that the medication used to treat this pulmonary illness can be deadly.

Around this time, L.G. Puckett employed a building crew that constructed many of the houses in Henson Hills and on Reeser Street. For the next eight years, Bruce worked for Mr. Puckett, doing mostly cabinet work in the homes the building crew constructed. He was next employed by Ralph Masters at Masters Cabinet Shop on Henson Street in Livingston. Just one of the many jobs Bruce helped with at Masters Cabinet Shop was the beautiful detailed wood work over the doorways of the girls dormitory at Tennessee Tech. Some twelve years later, Ralph Masters closed his business, and it was then that Bruce and several other men from this area got jobs at Loughman Cabinet Company in Algood, TN, a division of Bank Builders Corporation headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri. In the Algood shop, beautiful grained woods such a birds-eye maple, mahogany, and oak, also formica laminated cabinets were built for banks, colleges and airports such as Orlando International Airport in Florida, and an airport in the middle of the desert of Saudi Arabia.

At the age of 62, Bruce decided it was time to retire, and even now at the age of 83, continues to stay busy on their 19 acre farm in the Allons community. He has an antique tractor that has the same tires on the front of it that were on it when it was new. He and Orvie Ruth still raise a very large garden every year. Over the years, he has also been a bee keeper, winning several ribbons at the local fair. He started out with one hive that grew to a total of twenty-nine. Mr. Floyd Davis was one of many who bought honey from Bruce on a regular basis. An interest in purple martins is something else Bruce enjoys. His grandfather, Seymour Barnes, always had purple martins, and that’s how he got interested in them. Last summer, Bruce counted at least 100 martins around the birdhouses he puts up each year in his yard.

As Bruce looked back at his growing up years, he recalls one of the things his parents always emphasized was to never tell a lie. Another thing they did not allow was eating between meals. And something else most children who grew up when he did knew all about was what he refers to as Peach Tree Tea. While doing the interview with Bruce for this story, I couldn’t help but wonder how it was to walk up and down Rock Crusher mountain to school and back home again every day. Personally, the only way I could do it would be the rest about 15 minutes after every ten steps. The next question that came to my mind is what about today’s children? How would they deal with not only the walk up and down Rock Crusher mountain each day, but what about sitting down together with the entire family present for at least two meals each day? How would a rule that there would be no eating between meals go over, or being taught to never tell a lie, knowing that if you did, you would definitely get a little dose of Peach Tree tea? Now that I think about it, I’ve decided that’s a plan we could all benefit from. It’s pretty obvious it worked well for Bruce Barnes.