Old

newspapers continue to be a really good source for stories, and when

Nola Mae Needham ran across this article she had saved from1992, she

gave me a call. The article, printed on January 29, 1992, in the

Herald Citizen Plus, was written by Mrs. Callie (Myers) Melton,

(formerly of Livingston), a retired school teacher/librarian, of

Cookeville. Callie has given me permission to reprint her article. Here

is Callie's story about Uncle Bush.

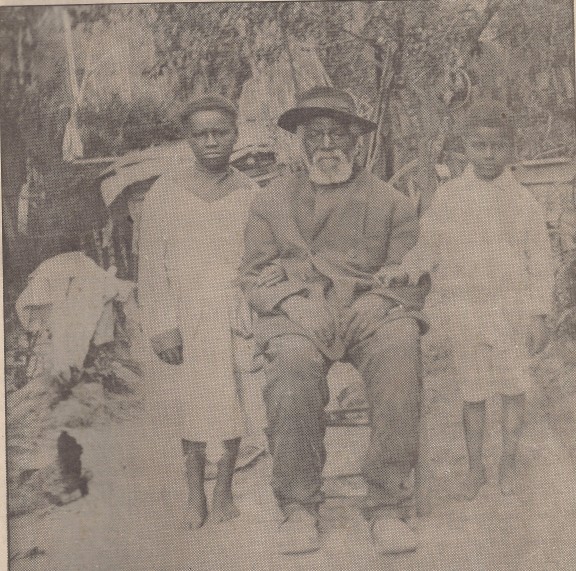

"My grandfather, Captain Luther Bigelow Myers, was like most of the

people in this area in his day and time. He owned slaves, but he did not

believe in slavery. So, sometime after he had moved with his family from

Old Fort Blount in Jackson County to the head of Roaring River in

Overton County just prior to 1855, rather than split a family apart, he

bought a female slave and her small son so she could be with her

husband. The Click family owned Siniah. She and Bush (I never did know

if the name was Bushnell or Bushrod, for it was always spoken Bush), had

a son, App, who always went by the name Click. I knew him in his old

age, and he was the spittin' image of Uncle Bush. But let me get back to

my story. Siniah and App lived with the Clicks, and Bush lived with the

Myers family until Grandfather Myers bought Siniah and App. When the

question of Bush and Siniah had come up, the only solution in

Grandfather's mind was that he must buy Siniah and the boy and bring

them to the head of the river. And that is what he did.

"Uncle Bush was a big man in his prime, not fat, just big-boned and well

muscled. He was soft-voiced and slow moving, but with a quick wit and a

kind and gentle nature. He was also a good and willing worker, so

Grandfather really needed him in this great undertaking. Moving from

Fort Blount to the head of Roaring River might not be far as the crow

flies, or even by ox-cart or wagon. But in the early 1850's, with plain

dirt roads and no bridges, it was something else. There could be no

visiting with the family left behind except maybe once a year, if things

went well.

"A log house consisting of two huge rooms with a kitchen set off in the

back was raised, almost literally, on the banks of the river. All the

out-buildings were raised too, between the house and the big

sweet-flowing spring a few hundred yards just west of the house site.

"The barn, the crib and the smokehouse, as well as the dwelling house,

were built of huge logs. I think they were of yellow poplar, but I'm not

sure, for they were worn slick with the years and the use when I was

born in 1911. The house was finished inside with wide dressed boards of

yellow poplar, and they too had taken on a mellow color from the years

and the use. Bush had helped erect all of these buildings, and took

great pride in the fact. He had helped get the huge stones that were

used to build the great chimneys in all the rooms, and had dressed the

big flat rocks that made the wide hearths.

"The horse lot around the barn was fenced with rails, as was the hog pen

behind the barn. Bush had helped to split the rails and lay the fence,

laying the worm (bottom rail) carefully in the new of the moon so that

it would lay on the top of the ground and be less likely to rot.

"Where Bush and Siniah lived, I never knew that either. I am sure that

they had a cabin somewhere on the place, where they had their own little

vegetable garden, and grew their own beans and pumpkins. I do know that

Grandfather always gave them a hog a-piece at hog-killing time. They got

corn from the corn crib for their bread, and plenty of milk and butter

from the family's cows. Siniah had her own corner of the big spring

house where she kept her crocks of milk, butter, souse, kraut, and

sulphured apples.

"Bush and Siniah had two more children after she moved to Overton

County. App still wore the name Click because his mother had belonged to

the Click family when he was born. But the other two children born in

Overton County, Jerry and Myra, were called Myers, the name of the

family who had owned their parents during slavery.

"Sometime before the outbreak of the War, Grandfather had freed Bush,

Siniah and the boy. They moved away from the Myers farm for a few years.

Where they went or what they did, I never heard, or even in my ignorance

thought to ask. But shortly, they came back to the head of the

river and asked to live with Grandfather again. He was glad to have them

back, and gave them a little piece of land that lay between the big road

that ran from the Myers Mill settlement at the head of the river to

Hilham, down towards Butler's Landing on the Cumberland River in Clay

County and the river.

"Grandfather gave Bush the lumber, and he and Uncle P helped him build a

tiny four-room cabin and barn. With palings, Bush fenced in a yard and a

truck patch, and with the rails, he fenced in his small corn patch, his

barn lot, and the little orchard just the east of the cabin. It was here

that Bush and Siniah lived until she died. Again, I have no idea of the

date, except I know that Jerry was about the same age as Dad, and Dad

was born in the year 1870.

"After Siniah died, Bush married Aunty Nancy, Aunt Nance, as she was

called. The couple lived in the same cabin and on the same piece of

ground until Uncle Bush died in 1921. When in 1921, I do not remember. I

don't even remember if it was summer or winter, but I do remember when

he died, for I was there and saw him leave this world so gently that it

was hard to say just what time it was when he departed. I do remember my

mother speaking of the clock and just what time he died. That was the

custom then, you noted the hour and the minute, as well as the month,

day, and year. Soon after his death, Aunt Nance moved to Algood to live

with Myra and her family. And slowly and surely the little cabin fell

into ruin.

"Uncle Bush had been such a part of the life of my Grandfather's family.

Uncle Bush's father had evidently belonged to Great-grandfather Phillip

Myers, and I am sure his mother had too, for Bush, age eleven, was

listed in the assets of Great-grandmother Mary White Cook Myers at her

death in 1845.

"Uncle P, my father's oldest brother, was born in 1852, and there were

ten children in all born into Grandfather's family. Uncle Bush

supervised their work in the fields, and taught them industry around the

house and barn. Grandfather was of German-Jew extraction, very

industrious, very particular about doing a job well, and able to do

anything from making the family's brogan shoes to fine furniture, to

black smithing, rifle making, and what have you. I today own two pieces

of fine furniture that he made between the years 1847 and 1849, and a

small sprig hammer that he turned out. A gun that he made is much prized

possession of distant relatives. So Bush was well trained, and he in

turn was very strict with the boys.

"But the children in my Grandfather's family were taught to love and

respect the blacks in the household, and woe be unto one who did not.

They were also taught that it was their responsibility to look after and

take care of the blacks. That philosophy was handed down to us in my

father's family. And when Uncle Bush's great-grandchildren sat in my

classroom at Algood High School in the years 1960 to 1966, that feeling

of love and responsibility was still there, on my side, at least.

"After Bush was too old to work anymore and provide for his and Aunt

Nance's needs, Dad always saw to it that they had plenty of meat from

his smokehouse and corn from his corn crib. Aunt Nance was quite a bit

younger than Uncle Bush, so she still made a garden, dried plenty of

beans, peas, and pumpkin, milked their own cow, and raised a flock of

chickens both for food and for barter at Uncle Bill's store, where she

got the little sugar, coffee, and salt that they needed.

"So many stories are told about Uncle Bush and the family, so many

stories that show how much mutual love and respect there was between the

blacks and whites in our family. One of the stories that I love the best

is the one about Uncle P and the beans.

"Now Uncle P was my father's oldest brother, and we loved him very much

for he was gentle and kind, with a sense of humor that charmed us all.

He would visit often. He lived over near Terrapin Ridge, so he always

stopped on his weekly visits to Uncle Bill's store, as well as just

coming

over to our house to visit now and then. In his later years, he often

reminisced about when he was a boy, and we would all hang breathless on

his stories.

"Uncle P said that when he was a boy, he had to work with Uncle Bush in

the fields. Now the blacks never ate with the whites under any

circumstances. That was just a way of life that was accepted by all. So

when Uncle P and Bush came in for dinner at Grandmother's house, Bush

took

his plate and sat in a chair by the hearth to eat, while Uncle P sat

with the family at the big long dinner table that ran almost the length

of the old kitchen. Uncle P didn't like the green bean hulls, so when

they had green beans, he would eat all the beans on his plate, then pass

the plate to Bush. Bush, on the other hand, like the hulls better than

the beans, so he ate only the hulls from his plate. Then when P passed

his plate the hulls on it, Bush passed his plate back to P with all the

beans on it. That was a ritual that went on for years between the two,

and it was fondly remembered by Uncle P when he was an old man.

"My personal memories of Uncle Bush and Aunt Nance are not many, but

they are very vivid, and they are a very integral part of my life. Us

young 'uns were not allowed to run out to Uncle Bush's whenever the

notion struck us. We always had to ask Mama. If she let us go, we were

alwaysreminded to watch our manners, to call out before we went into the

house, not to ask for anything to eat, even if Aunt Nance was baking

ginger cakes or frying turtle, and not to go to the orchard unless we

were told we could, and not to get in Uncle Bush's way if he was

working.

"As the oldest of my father's children, I was special to Grandmother

Myers. So when she was invited once a year to take dinner with Uncle

Bush and Aunt Nance, I was always included. Small as I was, I looked

forward eagerly to the big day. I washed and dressed, combed and plaited

as if I were going to meetin'.

"Then about ten o'clock, Grandmother would take up her parasol, and we

would walk out the path that went by the barn, across the spring branch,

and through the orchard out to Uncle Bush's house. When we got there, we

were usually met at the door by Uncle Bush, for Aunt Nance would be busy

in the kitchen. We would sit in the big room and talk with Uncle Bush

and

Bryson while Aunt Nance and Myra finished up dinner. What was served, I

only remember that once or twice it was turtle. Uncle Bush loved to fish

and there was fish-a-plenty and turtle too at that time in Roaring

River. And he was a master hand at dressing out a turtle, for he knew

just where

each of the seven kinds of meat was located.

"And Aunt Nance, like all black women, was a powerful good cook. I do

remember that her table looked like our table at home when the circuit

rider came, starched, white tablecloth and all. Her cutlery was the same

as ours, steel three-tined forks and wide-bladed knives with bone

handles,

plates with gold rims and flowers in the center, and tumblers that I am

sure now were dish order.

"Grandmother always asked the blessing, and then she and I ate while

Aunt Nance and Myra waited on us. The family ate later, for even though

we were guests in their home, the old rule was followed. After dinner,

Grandmother visited awhile with Uncle Bush and Aunt Nance, while I sat

and listened and looked around. On the walls were several enlarged,

framed photographs of blacks that I had never seen. I always wondered,

but never asked, who they were, and to this very day, I still wonder.

I'd give my eye teeth to know. Finally, in the middle of the afternoon,

Grandmother would say our thanks for a good meal and we'd take the

path home, pausing

only at the spring house for a cool drink and a look over in the hog pen

at the winter's supply of hams, bacon, and sausage still yet on the

hoof.

"The blacks came often to our house, but they always came by the back

door, and sat near the wide hearth in the kitchen. They might share

something with us, or we shared something with them. But mostly, they

came just to see if all was well, or if there was a need. Grandfather

had

long since been gone, and though my father looked after the family well,

Uncle Bush felt that "the Captain" expected him to still look after

"Miss Mary" and the children. Uncle Bush's family were the only blacks

in our settlement. He were highly respected by everyone, and they in

turn

treated each person with respect. When Uncle Bush was baptized shortly

before his death, most all of his white neighbors were there. A black

preacher came down from Livingston now and then to preach at the little

cabin, and many whites attended. And it was two white neighbors who

helped the old man walk down the hill from the cabin to the river so he

could obey the gospel, then made a pack-saddle and carried him back up

afterwards. When he was laid to rest in the Wilson graveyard, the hill

was covered with white friends who mourned his passing. Uncle Bush was

just a simple black man who had lived a long life, born a slave, but

lived to enjoy emancipation. He did no heroic deeds, nor did he amass

wealth, but he did something more important ... he lived a good, honest,

God-fearing life, showing kindness to all who crossed his path. What

better epitaph could any man want?"

Callie invites comments, letters, telephone calls, or visits to her home

located at 1275 East White Oak Drive, Cookeville, TN 38501, telephone

number 931/520-7016. Thank you, Callie, for allowing me to share your

story and memories of Uncle Bush.

Many will remember a grandson of Uncle Bush everyone knew as Charlie

Myers. Charlie’s obituary reads as follows:

Funeral services for Mr. Charles Whitson "Charlie" Myers, 91, of

Livingston were conducted at 1:00 p.m., on Tuesday, February 22, 2005,

from the chapel of Speck Funeral Home, Livingston, TN, with burial in

Bethlehem Cemetery of Livingston. Mr. Myers died February 18, 2005, at

Livingston Regional Hospital. He was born August 31, 1913, in Overton

County to the late Jerry Myers and wife Amanda Wilson Myers. He was a

press operator at Livingston Shirt Factory. He was a member of the

Cookeville Christian Fellowship and a member of the NAACP. At the time

of his death, he was survived by sons, Jerry Myers, Dr. Danny Myers;

daughters, Charlene Darty; Betty Coleman; Eleane Hogan; Shannon Benson;

11 grandchildren; and 19 great-grandchildren.

He is preceded in death by his parents; his wife, Mildred Elease

Copeland Myers; sons, Harold and William Myers; sisters: Marie Andrews,

Melissa Cullom, Ella Hill; Sally and Minnie Myers; and brothers Sidney

and Ben Myers. His grandsons served as pallbearers.